Gottfried Semper was the architect for a number of important buildings such as the Dresden Opera and the ETH Zurich building. He also is jointly responsible for the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Naturhistorisches Museum and the Burgtheater in Vienna.

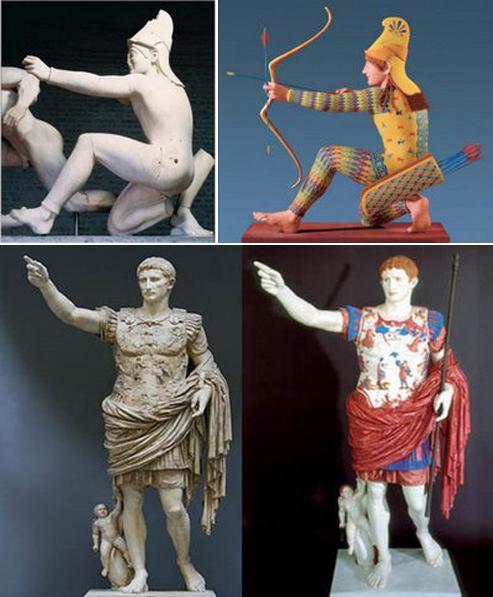

As well as an architect he was a theorist and researcher. Capable of original thought and an iconoclast he was a key proponent of polychrome architecture and statues in antiquity. At the time theorists and researchers refused to believe that Roman and Greek statues were in reality painted in many colors to be as lifelike as possible.

Ancient Roman and Greek buildings were also very colorful. Still to this very day the art and architecture of Rome and Greece is imagined to be very sedated and white whereas in actuality it was a riot of colors. Even contemporary movies and shows featuring Rome and Greece often imagine all the surfaces to be a calm and anaemic white.

This hampers our understanding of the Romans and Greeks. We can’t help but see them as somehow clinically detached aesthetes. On some level, Rome will always feel like some ancient space station where “great men” calmly walked on every street corner. White, clean, scarcely populated and quiet. Royal slippers side by side soft clicking set to a measured debate. The riotous multicultural chaos where people of every hue mingled (albeit not all equally, but this at least was a theoretical possibility for many) is unimaginable for many of us. Fascists often borrowed Roman grandeur replete with the clean and “pure” lines to give power to their rallies or buildings. It is unclear to what extent their borrowing was driven by pure esthetics or by the mistaken belief that ancient Rome was some kind of white Aryan populated operating theatre.

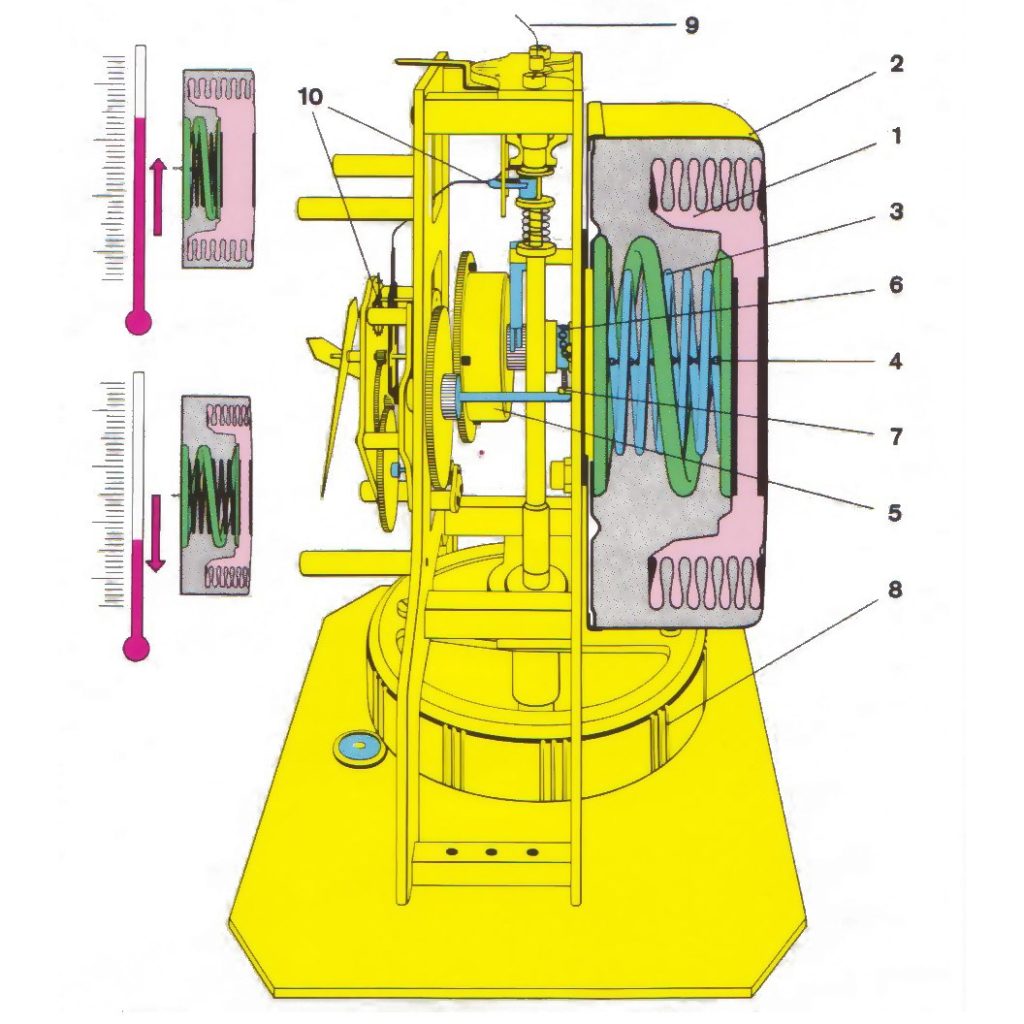

In addition to some very significant works in paper and stone, many of Semper’s ideas have always intrigued. The one that grabbed me the most is stoffwechsel. Stoffwechsel is the idea that an object’s purpose will shine through, throughout successive changes in the material. The surface of an object could have patterns, shapes or texture of some kind. A new manufacturing process would then come of age. This process would not need these vestigial patterns, but they would be included anyway.

The classic example of this is wall coverings. Previously carpets were used as wall dividers in houses. Later on, new building techniques saw walls being used. These walls were then covered in tapestries to provide for isolation while simultaneously evoking the same look of previous rooms. In a later period, 16th-century wealthy people replaced wallpaper with floor to ceiling paintings. Then stone walls where developed and these were often covered in wallpaper. This wallpaper gave a blank plastered wall similar and familiar geometric patterns and warmth as the previous generation tapestries. Later on, we see bricks get replaced (in some cases) with concrete. The concrete is however given patterns to appear to look like bricks.

Gottfried Semper’s theory of stoffwechsel is not widely referenced today (Please do correct me if I’m wrong, I have rarely come across him). Although in some quarters his work is revered more contemporary architects have replaced him in the collective mind’s eye. By firmly rooting architecture as an (at least partial) expression of communities driven by ritual and habit, Semper firmly roots architectural practice in history. By knowing him, we see architecture a little less as “great men drawing” and much more as a practice driven development within society as a whole. In Semper’s architecture, there are constraints, communities, practices and solidified ideas contained within a specific time. As we, hopefully, come down a little from our pedestal starchitect world. A more humble and humanistic view of architecture such as Semper’s would in my mind be more fitting.

I’ve always felt that some starchitects made buildings to build their portfolios rather than homes or spaces that worked for the customer or the public. The result is an architecture that is pure Ego over function. Architectural awards have always struck me as analogous to giving surgeons points for the beauty of the scars they leave behind. Yes, it may very well matter, but the health of the patient matters more. By rooting architecture as a product of time and place while seeing patterns of vestigial structures repeat themselves through different materials and technology paradigms Semper gives us an architecture that to me feels real and expressive. Materials and history to a certain extent dictate form. While at the same time, to me, it feels comforting that the patterns and practices that surround us are lines of history signalling past technological shifts and the familiar. The room I’m in is not as a space drawn by a “macher” but rather a space communicating its current place and past patterns. It is as if every building is not only a statement but also a timeline showcasing past paradigms and shapes back to the beginning of building itself.

Some conservators removed pigment and paint spots from Roman and Greek statues. So convinced were they that these were meant to be white that they took scalpels to historical evidence so that the statue would conform to their idea of them. We still do this. In 3D printing houses, we are trying to recreate past shapes with new technology. A drawing and idea become the jumping off point to developing a technology. Brick houses, ideas and patterns are being made with 3D printing. The old paradigm is still in the driving seat esthetically, as is the old way of doing things. There are a lot of renderings and overclaim in the 3D printing houses business, and not a lot of actual buildings. Stoffwechsel is not just now driving a wall covering but firmly in the driving seat of the overall design with brutalist ideas and fanciful idiocy now possible with new technology. Rather than look at improving functionality or making better homes silly drawings are being printed. Some startups do seem focussed on functionality and technology, but most look for something space aged and then run with that.

If we honestly looked at how a 3D printed building could be made in the least expensive way possible we would then have to change our ideas to match reality. The most optimal building would be a self-supporting dome. In this way, no supports or support materials would be needed, and prints would be quick, and all be in one layer with no lifting or retraction required. For many types of building, design retraction is not needed, and it is precisely these forms that can be printed the quickest, safest and cheapest. Doors and windows could be cut out of the dome form after the fact for example. Alternatively, a complete technical core of a building could be made offsite and lowered through the oculus. In that way, this cylinder could contain all of the water, electricity and other technical parts of the home and even be serviced or replaced centrally. Is this the be all end all idea of Additively Manufactured Architecture? I hope not, but it is at least an idea grounded in the process and limitations of the process that hopes to be efficient.

Lack of process understanding by architects and an idea lead approach is causing people to have to develop completely unnecessary features in 3D printers and unnecessarily raising the cost of 3D printing. Please let’s let the engineers run it this time?

Design for Additive Manufacturing and optimising design choices from the start for 3D printing is where smart companies are now placing their efforts. Designing with constraints and advantages in mind is how rewards can be reaped. Its as if we’ve designed a roller ball pen and everyone is obsessed with making it look and work as a pencil does. I love stoffwechsel as a concept for viewing ceaselessly into the past, but it should not guide architecture’s future.